Exit taxes are not new, but their modern structure has evolved over the past century.

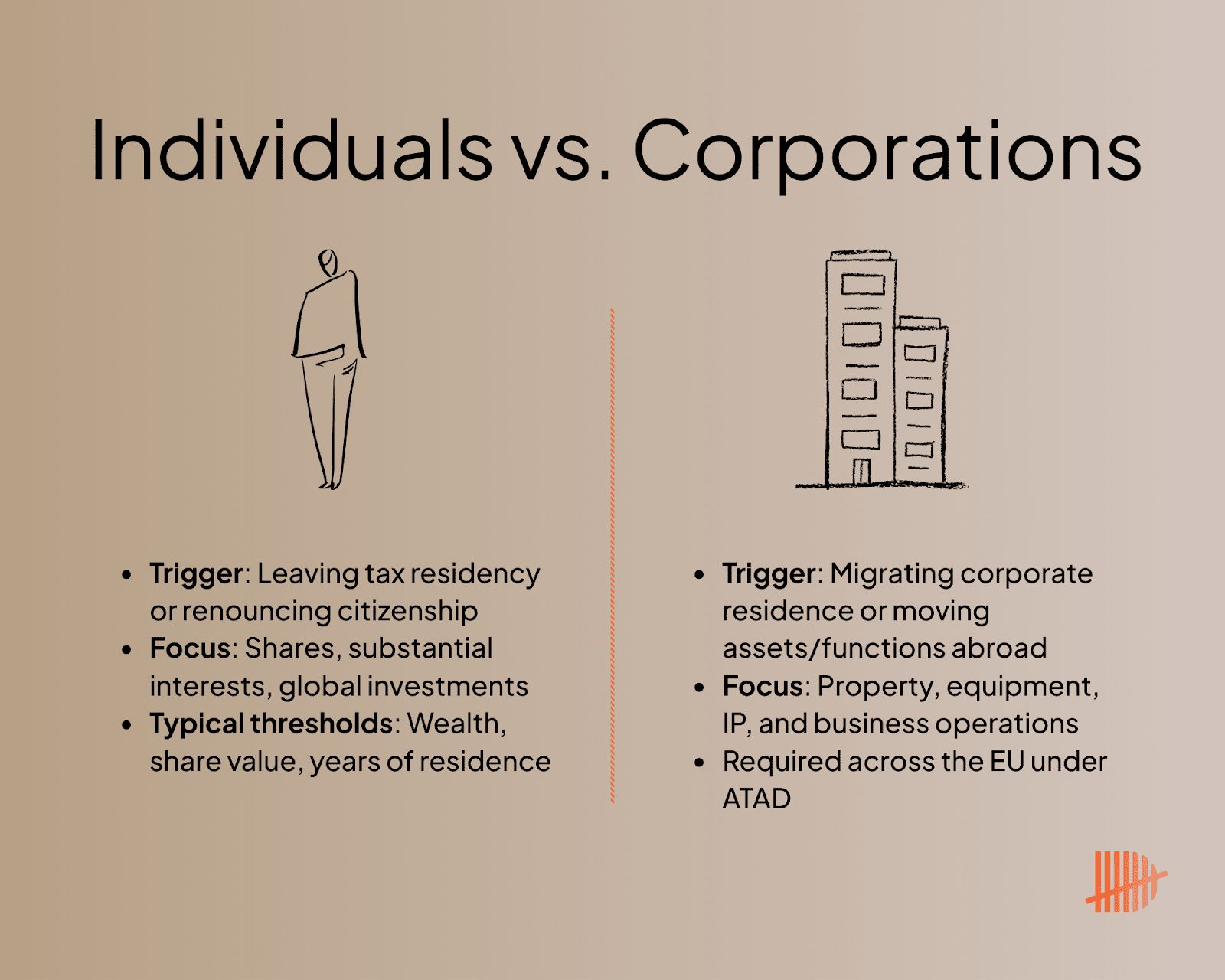

Mid-20th century – Corporate focus

Governments first developed corporate “toll charges” to stop companies from shifting appreciated assets offshore without paying tax. These early rules laid the foundation for later exit tax frameworks.

1960s onward – The emergence of individual expatriation rules

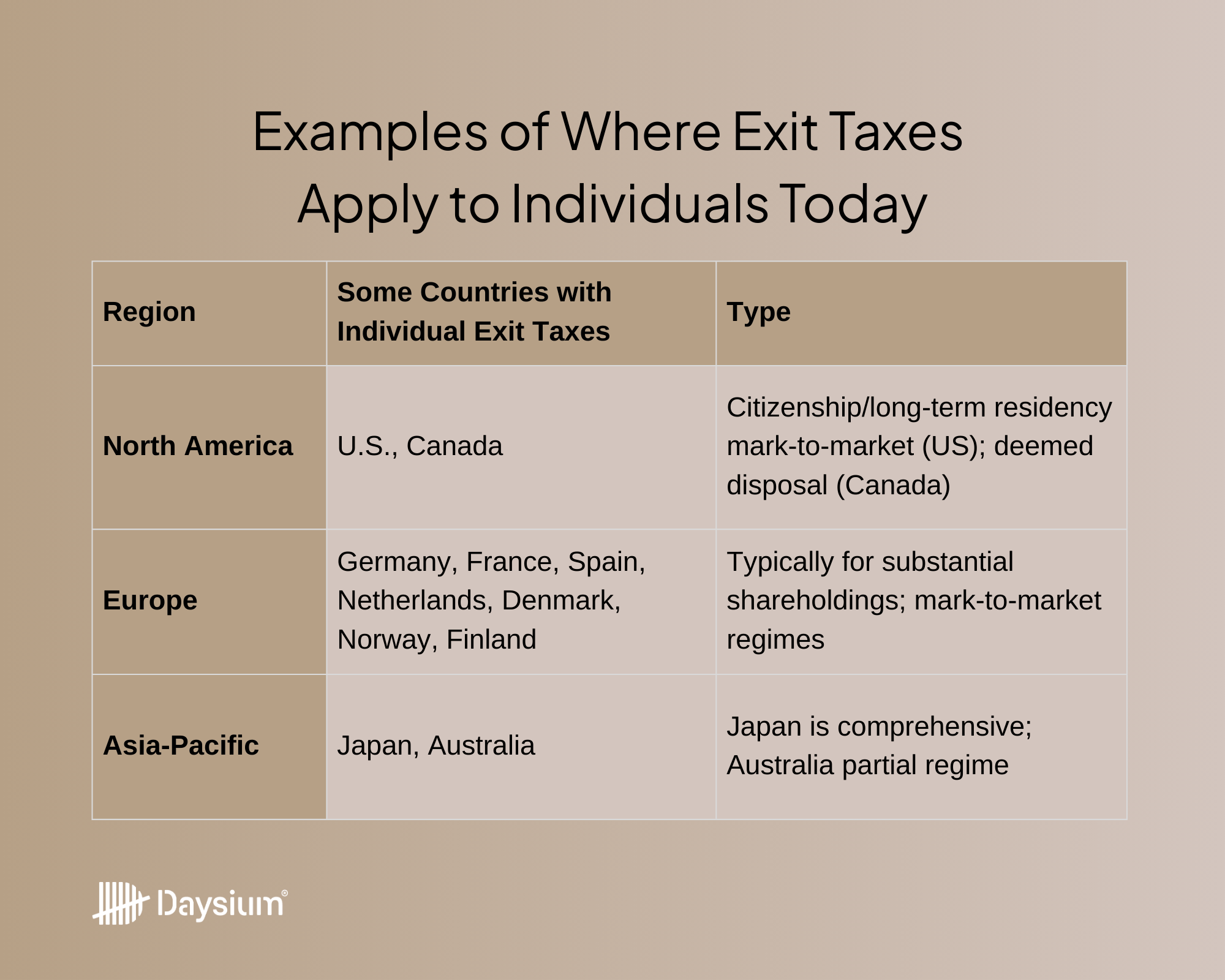

The United States introduced its first expatriation regime in 1966 under the Foreign Investors Tax Act, targeting individuals who left the US for tax-motivated reasons. Congress refined and strengthened these rules over the following decades.

Around the same time, countries such as Canada and Germany established their own departure or exit tax regimes for individuals in the early 1970s, taxing unrealised gains when residents emigrated.

2000s onward – Global spread and tightening

In the 2000s and 2010s, individual exit taxes became more common as global mobility increased and governments focused on taxing wealth where it is created. Many high-tax jurisdictions introduced or expanded exit tax rules for substantial shareholdings and private businesses.

At the same time, the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD), adopted in 2016, required all EU Member States to implement corporate exit tax rules, further embedding the principle that latent gains should not migrate untaxed.

| Did you know? The US HEART Act covered expatriation and imposed a mark-to-market tax on unrealised gains above a threshold, and it has strongly influenced individual exit tax designs. |